Faith on the Frontier: The Churches That Help Tell Brisbane’s Story

Before Brisbane had grand civic buildings or formal town squares, it had churches. In the mid-1800s, as Brisbane shifted from penal outpost to emerging colonial capital, faith communities were among the first to construct permanent buildings. These churches were not only places of worship; they were meeting halls, schools, gathering points and anchors of stability. Through them, we can trace Brisbane’s growth from compact river settlement to expanding agricultural districts shaped by migration and ambition.

St Stephen’s Chapel (1850) stands as the oldest surviving church building in Queensland. Built only a decade after free settlement began, this modest stone chapel signalled permanence in a town still defining itself. Many of its early parishioners were Irish migrants, and its presence reflects both the strength of Catholic communities and Brisbane’s transition from temporary outpost to enduring settlement.

St Stephens Chapel - from Pilgrims of Hope

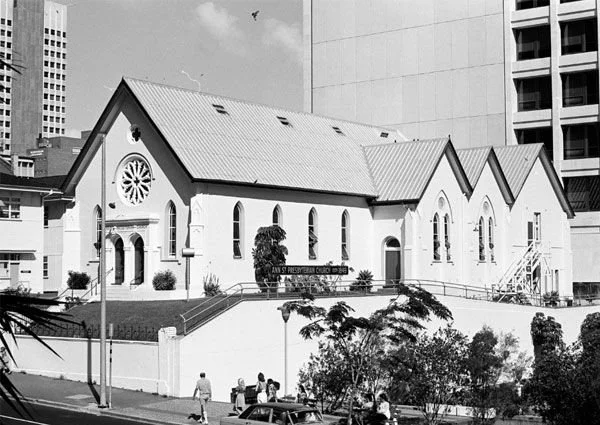

Ann Street Presbyterian Church (1858) reflects the rapid population growth of the late 1850s and the influence of Scottish migrants in shaping civic life. Its substantial Gothic design demonstrates a community confident enough to invest in enduring architecture. By this stage, Brisbane was no longer a frontier camp; it was becoming a structured town with diverse congregations and organised social institutions.

from Brisbane City Hall Heritage Trail

All Saints Anglican Church (1862) represents the established Church of England during a defining moment in Queensland’s history. Built just after Queensland’s separation from New South Wales in 1859, it reflects Brisbane’s emerging status as a colonial capital. Its permanence and position in Spring Hill speak to the close relationship between Anglican leadership and civic authority in the early colony.

All Saints church - from Brisbane Open House

By the late 1860s, Brisbane was no longer confined to its original town boundaries. River transport, emerging road networks and expanding agriculture were drawing families south toward the Logan River, west toward Moggill, and north into the Pine Rivers district. As settlement pushed outward, communities did what they had done in the town centre a decade earlier — they built churches. These buildings marked more than faith; they signalled confidence, continuity and the formation of stable rural societies beyond the colonial core.

St George’s Anglican Church (1875) represents the early arrival of Anglican community life in the Logan River district. Built as the town’s first permanent Anglican church, it illustrates how faith communities followed settlement and industry into rural Queensland. Its survival at the Beenleigh Historical Village preserves the story of mid-19th-century rural life.

Bethania Lutheran Church (1872) tells a powerful migration story. Founded by German settlers along the Logan River, it represents the cultural and religious traditions migrants brought with them and preserved in a new landscape. Its survival speaks to the continuity and resilience of those early communities, adding a vital multicultural dimension to Brisbane’s heritage narrative.

Moggill Methodist Church (1868) illustrates the spread of rural faith communities west of Brisbane. Serving farming families along the Brisbane River, this timber church reflects how small settlements established social cohesion and continuity through faith, long before municipal infrastructure arrived. It remains a tangible reminder of early pioneer life in the area.

T

Bethania - from Church Histories

St George Anglican- from Church Histories

Moggill Methodist - Built by the man with one leg – History Out There

Together, these six churches chart a clear pattern: consolidation in the 1850s town centre, confidence and denominational growth in the 1860s, and outward expansion in the 1860s–1870s shaped by agriculture, migration, and regional development. They are not simply old buildings. They are markers of how Brisbane grew — along rivers, through farming districts, and via the ambitions of diverse communities who chose to build for permanence.

Today, these churches remain part of the living fabric of Greater Brisbane. Some continue as active congregations; others stand as treasured landmarks within their communities. All of them remind us that heritage is not only found in grand civic monuments, but in the quieter places where everyday lives unfolded. By recognising and sharing these stories, we deepen our understanding of how Brisbane became the city it is today — and why protecting its historic places still matters.

BLH acknowledge that this article does not take in all of the Places of Worship across Brisbane. This article hopes to provide a taste and inspire exploration.